Sometimes it just takes one man’s vision to illuminate the

obvious. Muscatine, Iowa is a long way from Hamburg, Germany. The hard

labor of a farmhand must have seemed a daunting proposition to newly arrived

immigrant J. F. Boepple. Legend has it that Boepple was wading through

the shallows of an Illinois stream when he cut his heel. Reaching down,

he brought up the offending mussel shell and realized it was similar in

size and shape to the sea shells he had used for buttons back in his native

Germany. If it was strong enough to savage his foot it was strong enough

to create a button. A multi million dollar industry was born.

BOEPPLE FULFILLS HIS DREAM

It’s

a good story and it may have happened just like that, but in truth Boepple

came to America looking for freshwater mussels suitable for the button

trade. It’s known that he received samples of American mussels while

still making buttons in Germany. His quest led him to Muscatine, Iowa;

he must have stood on the riverbank amazed. A seemingly endless supply

of shells there for the taking; yellow sandshells, pistolgrips, ebonyshells.

It was an incredible natural resource, the great mussel beds of the Mississippi

River.

It’s

a good story and it may have happened just like that, but in truth Boepple

came to America looking for freshwater mussels suitable for the button

trade. It’s known that he received samples of American mussels while

still making buttons in Germany. His quest led him to Muscatine, Iowa;

he must have stood on the riverbank amazed. A seemingly endless supply

of shells there for the taking; yellow sandshells, pistolgrips, ebonyshells.

It was an incredible natural resource, the great mussel beds of the Mississippi

River.

He noted in his autobiography, “At last I have found what I had been

looking for; yet there still was a problem before me. I was without

capital in a strange land among strange people and unfamiliar with

the language.”From Boepple’s first crude, foot driven lathe the trade

blossomed into one of the largest and most profitable fisheries in

the inland United States. Sixty button factories lined the banks of

the Mississippi near Muscatine Iowa by 1899. Ten years after Boepple’s

inspiration, the industry supported thousands of workers. Its value

was calculated in the millions of dollars. The future looked bright

for communities along the Mississippi.

LIFE OF THE CLAMMER

Clammers

To supply this industry, the lifestyle of the clammer immerged.

An itinerant flotilla of shanty boats worked the mussel beds. The clammers,

like river men everywhere, were a colorful lot. They could make good money

if they were on a new bed, up to ten dollars a day. And there was always the

possibility of finding that life changing pearl. Clammers answered to no one

but themselves; unsavory “mussel camps” sprung up overnight. Local residents

complained about the ripe odors as the clammer boiled their catch to open the

shells. But the town folk didn’t complain about the money coming into their

communities. Muscatine had the feeling of a boom town as the industry flourished. All

it took to put a clammer in business was a small boat and crowfoot, an iron

bar with a few dozen hooks attached. As the tool was dragged across the riverbed,

mussels instinctively snapped down upon contact with the hook. It was

devastatingly effective. Downriver from Muscatine, a one and one half mile

section of river gave up ten thousand tons of shells. By 1898 this bed, one

of the most productive on the river, was gone. The clammers simply moved on

to the next bed on the river.

Muscatine Factory and Cut-out Mussel shell

The demand for freshwater mussel shells kept growing. Orders were pouring

in from all parts of the United States, huge shipments of buttons made their

way across the Atlantic to Europe. Automated button manufacturing equipment

accelerated the process. An estimated 11.4 million buttons were produced

from freshwater mussel shells in 1904. Ten years later 21.7 million buttons

went to market. Production peaked just a few years later when 40 million

buttons were produced in 1916. At that time there were twenty thousand people

employed in the button industry. These were good jobs with regular wages,

a real economic boost to local communities. But the boom couldn’t last.

Workers at the Muscatine Button Co.

JUST GROW MORE MUSSELS

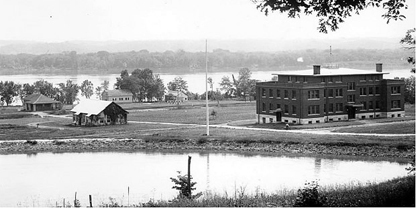

Fairport Biological Station

Intense, unregulated harvest quickly depleted the larger mussel beds.

In 1907 the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries stepped in to try to protect the industry.

Two biologists from the University of Missouri were engaged to prevent the

“commercial extinction” of freshwater mussels. George Lefevre and Winterton

Curtis began the complicated task of creating an artificial propagation program.

Curiously, but perhaps telling for the times, no serious effort was made to

regulate the freewheeling itinerant clammer with their devastating iron crowfeet

dragging up and down the river. The solution was simply to propagate more mussels,

not to regulate the harvest. Lefevre and Curtis published the results of their

research in the Journal of Experimental Zoology in 1910. The project

was a success; they had developed a method to artificially propagate mussels.

The Bureau of Fisheries, under the direction of Robert Coker, began commercial

scale propagation of freshwater mussels in 1912 at the Fairport Biological

Station. They concentrated on the Upper Mississippi. The object was to bring

the juvenile mussels up to “planting size”. Like an agricultural crop, mussels

would simply be planted in the river for later harvest. Over one billion juvenile

mussel “seeds” were produced. But as scientists at the Bureau of Fisheries

soon learned, the problem was not with the seeds, it was with the ‘farm’ itself.

New agricultural practices added silt to the rivers, sewage from the nation’s

new cities polluted the water. The rivers were becoming unsuited for juvenile

mussels. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers planned dams on the Upper Mississippi,

effectively stopping host fish from facilitating new mussel beds. By 1930,

the Bureau of Fisheries ceased its mussel propagation program, going as far

as recommending that the states repeal the limited harvest regulations they

had enacted. The Bureau gloomily reported, “It appears that the mussel fishery

on the Mississippi River is doomed to economic exhaustion” and urged that

the industry harvest the remaining mussels before they were killed by silt

or pollution.

J.F. Boepple died a poor man. He’d watched as the industry created by his vision blossomed into a powerful economic engine. He then watched it falter as the resource that fueled this engine vanished. At the end of his life, Boepple was working with the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries, trying to protect and conserve the natural resource that had been so pivotal for him; the freshwater mussel. Sometimes, one man’s vision can have unforeseen consequences.